“Nuove” geometrie nei Concept per l’Home Design

|

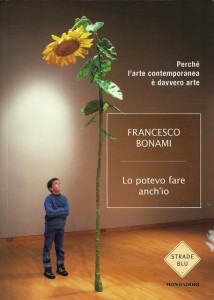

“Lo potevo fare anch’io” è l’affermazione che a volte ci verrebbe di pronunciare di fronte ad alcune opere d’arte contemporanea perché ci sembrano così spontanee e quasi a portata di mano che nulla di difficile e troppo impegnativo pare sia stato speso per realizzarle.

E’ da questa affermazione che parte Carlo Bonami (Senior Curator al Museum of Contemporary Art di Chicago, Direttore Artistico di Pitti Immagine Discovery e curatore di numerose delle più importanti rassegne d’Arte al mondo) per tracciare una breve quanto piacevole mini-storia dell’Arte contemporanea per dimostrare perché in realtà non è così vero che potevamo farlo anche noi. Traslando la domanda dall’Arte alle Arti (applicate) la domanda che mi sorge di fronte a certi pezzi di Design, non senza un po’ di invidia, è “Questo avrei voluto farlo io!”.

Questa mia ammirazione non scaturisce da pezzi unici ed incredibili dell’Industrial Design, come magari una Ferrari rossa fiammante, ma è legato a pezzi semplici quanto innovativi, progetti che da sempre definisco SMART. Per spiegarmi meglio, ve ne illustro direttamente uno che ho trovato di recente nel Web.

Si tratta del D-Table, un tavolo con infinite possibilità di forma. Questo tavolino da salotto, infatti, grazie ad un semplice sistema di cerniere e di rotelle può cambiare la forma, come un Tangram, passando da un perfetto quadrato ad un triangolo equilatero attraverso un numero pressoché infinito di posizioni intermedie. Il Design alla base è ispirato al Problema di Haberdasher, un rompicapo geometrico che consiste nel trasformare un quadrato in un triangolo equilatero.

Questo tavolino dunque, sebbene con una finitura un po’ cheap, quasi da IKEA, è un oggetto da una parte molto semplice e statico (un quadrato e un triangolo equilatero sono forme molto equilibrate), ma dall’altra rivela sempre nuove configurazioni: se prendo il thè in salotto sarà un quadrato, ma se invito gli amici per una festa posso trasformarlo in un pezzo allungato da mettere in un angolo, in modo che non intralci il passaggio. Tutte queste possibilità sono contenute in uno stesso oggetto che posso muovere e modificare facilmente da solo. Alla semplicità dello schema a 2 dimensioni di un Tangram, i giovani designers del D-Table aggiungono degli utili (det)tagli, come il foro porta-vaso o le fessure portariviste che possono ispirare nuovamente differenti usi e configurazioni. Ebbene, tornando al mio interesse nel Design di piccoli spazi, trovo l’applicazione di un rompicapo geometrico, nato dalla mente del matematico Henry Ernest Dudeney nel lontano 1903, ad un piccolo tavolo da salotto che sta benissimo in una casa moderna dei nostri giorni, un’abilità quasi geniale da parte dei progettisti di www.thedhaus.com.

Un Concept molto chiaro, un puzzle 3D che trasforma un quadrato in un triangolo mediante dei tagli precisi e sapienti, che applicato ad un pezzo di arredamento diventa pratico, flessibile e multifunzionale e con una varietà di usi che lo possono rendere un classico del design di interni:”Avrei proprio voluto farlo io!”. A corollario di questo Teorema di Design e Geometria c’è però la considerazione che lo stesso principio, applicato all’Architettura, diventa elefantiaco e pressoché impossibile: se da un lato, infatti, la flessibilità e le diverse sfaccettature geometriche potrebbero rendere un edificio basato sullo stesso Concept, variabile e multiforme nella realtà, non c’è nulla di più insensato ed irrealizzabile di una casa poggiata su dei binari che ipoteticamente ruoti e si sposti su di essi, magari alla pressione del tasto di un telecomando.

L’idea naturale ed organica di alcune forme geometriche incernierate che si trasformano a seconda delle necessità è dunque una soluzione “smart” per un piccolo tavolo di 70cm di lato realizzato in legno, ma se riportata alla dimensione di una villa a due piani perde il suo contatto con la materia reale e diventa impraticabile se non impossibile. Un Concept diventa Design solo se declinato con sapienza ed equilibrio.

“I could have done that too” is the claim that sometimes We would would like to say in front of some contemporary works of art because they seem so spontaneous and almost at hand that nothing too difficult and challenging seems to have been spent to achieve them. From this statement Carlo Bonami (Senior Curator at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago, Artistic Director of Pitti Immagine Discovery and editor of several of the most important exhibitions of art in the world) draw a brief but enjoyable mini-history of contemporary art to prove that it is not true that we could have done it too. Shifting the demand from Art to the Arts (Applied) the question that is in front of certain pieces of design, not without a little ‘envy, is “I wanted to do it myself.” This admiration is not based on unique and incredible industrial design, perhaps a flaming red Ferrari, but is tied to simple pieces as innovative … projects that I always call SMART. To explain better that I’ll show you one that I recently found on the Web That’s the D-Table, a table with endless possibilities of form. This coffee table, in fact, thanks to a simple system of hinges and wheels can change the shape as a Tangram, from a square to a perfect equilateral triangle through an almost infinite number of intermediate positions. The design is inspired by the Haberdasher problem, a geometric puzzle that consists of transforming a square into an equilateral triangle. This table, although with a cheap finish almost IKEA style, could be very simple and static (a square and an equilateral triangle shapes are very balanced), but on the other hand reveals new configurations: if I take a tea in the living room it will be a square, but if I invite friends to a party I can turn it into an elongated piece to put in a corner so that it does not obstruct the passage, all in one and the same object that I can move easily and change alone. The simplicity of the 2-dimensional pattern of a Tangram young designers of the Table D-plus earnings details as the port-hole pot racks or slots that can inspire different uses and configurations again. Well back to my interest in the design of small spaces I find the application of a geometric puzzle, born from the mind of a mathematician Henry Ernest Dudeney in 1903, a small coffee table that looks great in a modern home of today a skill almost genius on the part of designers www.thedhaus.com. A very clear concept, a 3D puzzle that transforms a square into a triangle by the precise cuts and wise men, who applied to a piece of furniture becomes practical, flexible and multifunctional, and with a variety of uses that can make a design classic of Interior … “I just wanted to do it myself.” The corollary of this Theorem of Design and Geometry, however, is that the same principle applied to architecture becomes bloated and impossible: on one hand, the flexibility and the different geometrical facets could make a building, based on the same concept, variable and multishape, but there is nothing more foolish and impractical for a home resting on the tracks that supposedly rotates and moves on them even when you press a remote control. The idea of some natural and organic hinged geometric shapes that are transformed according to the need is therefore a smart solution for a small table of 70cm side made of wood, but if given the size of a two-storey villa loses his contact with the real matter and becomes impractical if not impossible. A Design Concept becomes Real only if declined with wisdom and balance. |